The 5 Megatruths of Great Teaching

How fantastically big is this question,

‘What makes great teaching?’.

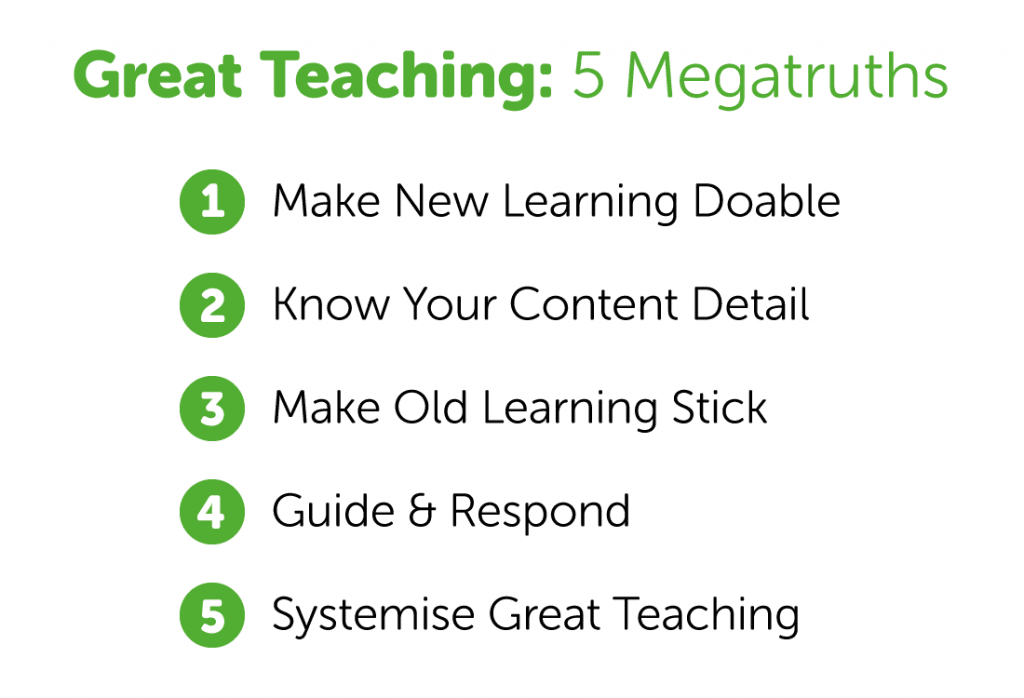

It’s quite a scary question for an actual teacher… because it challenges you to answer it! At first, it sounds rhetorical, and perhaps we would all feel safer if it was. The question seems to be asking you to explain your professional worth and even your professional qualification. If you are given a few moments to jot down some bullet point answers, then you may struggle. Why? Well, if we listen to John Sweller (the TES referred to him as the ‘Godfather of Cognitive Load Theory’), then we can’t even begin to know about great teaching until we know about how the brain learns. Sweller says, ‘Without knowledge of cognitive processes, instructional design is blind’. In other words, we need to know about the brain in order to teach. No wonder ‘great teaching’, then, is so elusive. The brain is, after all, the most complex structure known to humankind. In this post, we introduce you to… The 5 Megatruths of Great Teaching!

What Are We to Do Then?

There’s a huge twitter-sea of information and opinions out there these days, and it’s full of ‘schools’ of academics all vying for our attention. It’s a competitive environment. Big fish eat little fish. On the other hand, the sea is a beautiful place and if you’re a strong swimmer and you know where to look you might even find some sunken treasure. If you follow the currents, you might find Professor Rob Coe’s document entitled, ‘What Makes Great Teaching?’. With a rare, true intellectual humility, Coe and his team aren’t showing off their own research, they are simply trying to help us by shoving all the treasure chests from the bottom of the ocean together into one incredible meta-research pile. One doesn’t need to have carried out any research of one’s own, we can all dive straight down and find the treasures of great teaching. In other words, we can all easily access everything that the most knowledgeable brains on the entire planet know about great teaching. Now, if there was ever a point to the internet, it is exactly that. You can literally eat a quarter-pounder supersize meal, and, by the time you’ve slurped your last coke, you can gain all the killer information on the planet about what makes great teaching! Only the young will take that for granted. That’s amazing!

Just in case you’re too busy even for that, here is a quick ‘Instagram’ view of what that pile of treasure looks like. There is much more to be said about each one, but here, in one quick snapshot, are my 5 Megatruths of Great Teaching:

Megatruth 1: Make New Learning Doable:

At the heart of teaching is the ability to ensure learners acquire new skills, can understand new concepts, and recall new facts. In order to do this, we need to present the next small parts of the curriculum to the learner in a chronological way that they can grasp. For this ‘grasping’ to take place then the new content must be connecting to some prior knowledge that the learner is able to retrieve from their long-term memory. In this way ‘great teaching’ has considered the limitations of the brain’s working memory. So, with microscopic knowledge of curriculum content, we can reduce the cognitive load of the new learning… thus making it doable.

A key feature of this is to teach new content explicitly.

Megatruth 2 – Know Your Content Detail:

If Megatruth 1 is telling us we need to break the curriculum content down into small parts, then Megatruth 2 is all about whether the teacher has that curriculum detail in their mind. Knowing your subject used to be called subject knowledge! Subject knowledge always had a daunting ring about it. It made it sound like, for example, you needed to be a brilliant mathematician personally in order to be a great primary maths teacher. Not so. But you do need to break down the whole ‘big mathematics’ learning journey into small parts so that you can get to know the part you’ll be delivering really well. Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) guru Greg Ashman makes the point that ‘the key principle is to break things down, and to break things down into smaller bits than you think you need to’. This means there is a detail to the delivery that the learner really benefits from. This will need to include knowing any specific pedagogical approaches that arise from the particular nature of the subject or domain. As well as the teacher zooming into the detail of the moment it also requires the teacher to:

- have their head up and know what has gone before. We can think of this as earlier curriculum content but it is really the pattern of learning hardwired into the brain’s Long Term Memory (i.e. a ‘schema’) that the learner will be using/building upon/attaching to with the new content.

- know what will come further along in the learning journey, i.e. what today’s learning is doing for the future. Presumably, the new content itself is contributing to a schema, and not just in the hope that it will be used one day but in a well-thought-through CLT-inspired curriculum journey.

- prioritise core content as not all curriculum content is of equal value. Instant recall of tables facts, for example, will be more important (i.e. a more useful schema) than classifying triangles.

Megatruth 3: Make Old Learning Stick:

Just as we are feeling like we might actually be getting our heads round ‘great teaching’, along comes the realisation that there is no point getting children to do/understand/recall ‘new stuff’ if they don’t remember it! Remembering makes you clever. But, and here comes the nub, you can’t just wait and see if the kids remember it. It’s the teacher’s job and great teaching requires a full appreciation of what this entails. So, making new learning doable isn’t, after all, at the heart of great teaching (we thought for years that it was) but making it stick is! John Sweller tells us that if a teacher hasn’t changed the learner’s Long Term Memory then they haven’t learnt at all. Further to this, Soderstrom and Bjork (2015) argue that retaining and recalling the content isn’t sufficient, but that it needs to be transferable to new contexts as well. Great teaching never takes it’s eye off these two goals: ensuring retention and transferability of knowledge. When we look at the relationship between the first three Megatruths we could do worse than to lean on the succinctness of Craig Barton, ‘The working memory is the gateway to learning’.

Megatruth 4: Guide and Respond:

I hate to disappoint you, but, just as we were really beginning to feel like we have found the heart of great teaching, we start to realise that again the previous Megatruths are completely undone if you don’t have the skills to guide the learners from a to b. We’ve already seen the need to take learners into new learning at Megatruth 1, and to do that we need to know the curriculum content detail (Megatruth 2), and then we have the need to guide learners along the journey from Working Memory to Long Term Memory at Megatruth 3.

This guiding isn’t easy. You need to respond to the learner. In order to respond you need some information about whether their brain is grasping (Working Memory) and changing (Long Term Memory). Where will you get that information from? From their outcomes, but only when you: observe them; ask them questions; listen to them; challenge them; mark their work (eek!); analyse their data; etc. This is assessment in preparation for future great teaching. Which means it is assessment… for learning. Now that’s a phrase you may well have heard before! Dylan Wilian (another education Godfather) has gone on Twitter-record saying he wishes his coining of the term ‘Formative Assessment’ had instead been ‘Responsive Teaching’. Basically, that way it would have done what it said on the tin. Put another way, the theory of getting the cognitive load right is of no practical value if it isn’t combined with the actual teacher’s ability to guide learners to achieve through responding.

Megatruth 5: Systemise Great Teaching:

This fifth and final Megatruth hasn’t come from the same pile of academic treasure. However, when you look at the first 4 Megatruths then basic logic tells us that no one individual can achieve very much on their own. The success of learning (and therefore teaching) happens over a sustained period of time. In a school setting, there is literally no point in one teacher being great, including having a huge impact on the child’s Long Term Memory, if next year the teacher doesn’t know how to build on the schema that has been so hard won, and so hard fought. Ultimately, great teaching is a school leadership issue. Great teaching is only truly attained at the whole school level. ‘Whole school or not at all’ is the mantra.

This requires a curriculum journey that is designed, structured, and resourced in a way that is chronologically detailed and nuanced, yet is efficient to follow and easy to adapt to.

It would need to be accessed moment by moment (almost certainly digitally) and have an integral student-tracking system for core content that maps out a minimum, but high, expected standard journey that takes into account external accountability. Ironically, the more smoothly the students experience ‘getting the load right’ across a school, the easier it is to teach the next steps to more students through a common input. Great teaching reduces the need to adapt teaching, and with it, workload reduces too. This is a vital point; great teachers don’t work harder! Great teachers aren’t constantly shattered by the workload! No. Instead, great teachers work in great schools with great school leaders, that have put in place great CLT systems, that support only one thing… great teaching!

The 5 Megatruths of Great Teaching:

These 5 Megatruths aim only to simplify the complexity that is great teaching. Very often the simplicity isn’t enough, but at other times the simplicity is very helpful indeed. It can provide a perfect door opening into a new understanding, a teacher-training session, a lesson observation analysis, or even just a conversation starter. The 5 Megatruths can act as a simple lens through which to see the complex. And at least if anyone ever asks you, ‘What makes great teaching?’, then you have a simple entry point into the vast ocean that tries first to understand the brain, and from that tries to understand learning, and only from that tries to understand great teaching.

References:

Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S. and Major, L.E. (2014) What Makes Great Teaching? Review of the underpinning research. Available at www.suttontrust.com.

Rosenshine, B (2012). Principles of Instruction: Research Based Strategies That All Teachers Should Know, American Educator 36(1): 12-19..

Soderstrom, N. C. and Bjork, R.A. (2015). Learning Versus Performance: An Integrative Review. In Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Sweller, J., Ayres P. and Kalyuga S. (2011). Cognitive Load Theory: Explorations in the learning Sciences, Instructional Systems and Performance Technologies. (New York: Springer).

Barton, C. (2017) ‘Greg Ashman’, Mr Barton Maths Podcast.

Barton, C. (2018) How I Wish I’d Taught Maths (John Catt, Suffolk).